TAM GIBBS, AS I KNEW HIM

By MT (Steven) Rose

I had been living in Los Angeles studying the traditional Yang style Tai Chi when my brother, who had been studying Tai Chi with Martin Inn of the Inner Research Institute, gave me a typed copy of the Classics. Martin had translated the Classics for his students. When I read them for the first time, I had many questions. I went to my teacher and he could not comment on this written material. Shortly thereafter the Cheng and Smith book (T’ai Chi The “Supreme Ultimate” Exercise for Health, Sport, and Self-Defense) came out. While reading late one night I realized I wanted to study in New York at the Cheng Man-ch’ing school. I knew noone there so I called Martin, whom I had not yet met, and introduced myself as my brother’s brother and asked him to recommend the best teacher at the Cheng Man-Ch’ing school. With no hesitation he said Tam Gibbs.

I had been living in Los Angeles studying the traditional Yang style Tai Chi when my brother, who had been studying Tai Chi with Martin Inn of the Inner Research Institute, gave me a typed copy of the Classics. Martin had translated the Classics for his students. When I read them for the first time, I had many questions. I went to my teacher and he could not comment on this written material. Shortly thereafter the Cheng and Smith book (T’ai Chi The “Supreme Ultimate” Exercise for Health, Sport, and Self-Defense) came out. While reading late one night I realized I wanted to study in New York at the Cheng Man-ch’ing school. I knew noone there so I called Martin, whom I had not yet met, and introduced myself as my brother’s brother and asked him to recommend the best teacher at the Cheng Man-Ch’ing school. With no hesitation he said Tam Gibbs.

In the spring of 1977 when I arrived in New York, I called Tam and he was out of town on a teaching tour. When he returned my phone call he asked if I knew the short form, and I told him no. He told me he would be back in the fall and instructed me to learn the short form. I did that and when he came back in the fall, he told me when to attend class: 6:00 o’clock Sunday evening. When I first walked into class, there were only 5 people there: Harold, Richard, Stan, Carol, Filomena and myself. Tam had told me the wrong class. I was in the advanced class. The first thing he said was, “When beginning Tai Chi, the first thing that moves is the mind.” I fell in love with him on that day and studied with him until his untimely death in 1981.

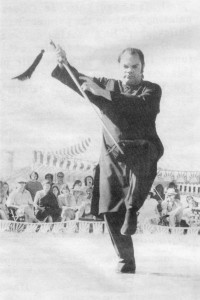

We shared the same birthday, and we celebrated his last birthday together. He wanted to include me in that celebration. There were 50 to 60 people at the celebration. I walked into the kitchen and he was standing there alone practicing ‘turn the body and sweep the lotus’. He asked me how many of those attending the celebration came to class. He gave a little chuckle and continued doing his lotus kick.

We shared the same birthday, and we celebrated his last birthday together. He wanted to include me in that celebration. There were 50 to 60 people at the celebration. I walked into the kitchen and he was standing there alone practicing ‘turn the body and sweep the lotus’. He asked me how many of those attending the celebration came to class. He gave a little chuckle and continued doing his lotus kick.

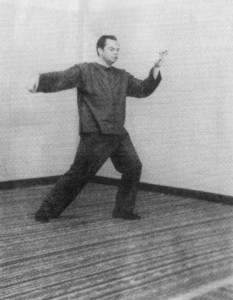

There was a saying around the school in New York, “Do not close the door too quickly behind the Professor. You might hit Tam in the face.” There is a Chinese painting of an older man and a little boy by his side. Tam always referred to himself as the little boy next to the old man. Tam started studying Tai Chi in the early 60’s with a student who had preceded Professor to New York City by the name of Da Liu. At the time, Tam was a student at Columbia University studying English literature when he observed Da Liu doing this strange practice which he later discovered was Tai Chi. Tam asked Da Liu if he would teach him this strange practice, and he said he would. After some time of studying with Da Liu he said to Tam, “I can’t teach you anymore. You have to study with my teacher.” The only problem was the Professor was living in Taiwan.

In the mid-60’s Professor came to New York City for an exhibition of his paintings. It was then that Tam met the Old Man. He told the story this way: The Professor, Da Liu and I were riding up in the elevator together. The Professor said to Tam through Da Liu, “Can I touch him?” Tam said that of course he could. The Professor put his hands on Tam and felt his shape and density. Tam then asked if he could touch the Old Man. The Professor responded in the affirmative and as Tam touched him, he felt a man who was shaped like a barrel. That was the beginning of the relationship between the Professor and Tam.

The Professor had two nicknames for Tam. The first was the ‘model’, someone after whom we should model ourselves. The second nickname he had for him is ‘the precious piece of jade inside the ugly stone’. To me, these nicknames described perfectly Tam. Unrefined looking, but highly cultivated. To follow his example how could you go wrong?

The Professor had two nicknames for Tam. The first was the ‘model’, someone after whom we should model ourselves. The second nickname he had for him is ‘the precious piece of jade inside the ugly stone’. To me, these nicknames described perfectly Tam. Unrefined looking, but highly cultivated. To follow his example how could you go wrong?

Professor moved from China to Taiwan and from Taiwan to New York. Professor wanted to plant the seeds of Chinese philosophy and culture through the teaching of Tai Chi Ch’uan to Westerners and decided that New York City was the place to do that. He wanted to take the teachings from the old Chinese philosophers and communicate that in a language that could be understood by Westerners. Tam understood deeply the Professor’s teachings and being an American, he could bridge the cultural and linguistic gaps and bring the essence of Professor’s teaching to English-speaking people. That was his great gift. Unfortunately, he died before many of us got that gift, and I consider it my great blessing to have known and studied with Tam Chester Gibbs. I love Tam and I miss him.

From the time Tam met the old man until his death in 1981, his sole purpose was to serve the Professor and clarify his profound teachings. It was Tam who held the Professor’s head while he died. Tam remained in Taiwan for some time after the Professor’s death. When he returned to New York, he went back to college finally getting his master’s degree in Chinese studies. He died at age 42 of a burst appendix just after founding his school “Tai Chi Center for Culture and the Arts.”

There was a two-week period between the time his appendix burst and the time of his death. It was a very difficult time for us at the school. He died on a Sunday night. We had class that night and people came from out of the woodwork to offer themselves as replacement teachers. I wasn’t alone in finding this distasteful. None of us were prepared for his untimely death.

There was a two-week period between the time his appendix burst and the time of his death. It was a very difficult time for us at the school. He died on a Sunday night. We had class that night and people came from out of the woodwork to offer themselves as replacement teachers. I wasn’t alone in finding this distasteful. None of us were prepared for his untimely death.

The night he died, Tam came to me in a dream. In the dream, Tam was in the family bed and with him were four other students and myself. I asked Tam, “Now that you’re dead, how do I proceed with my studies?” His answer was, “In the classical way.” That was the end of the dream. I have spent the last 31 years clarifying for myself what it means to follow the classical way.

Tam’s untimely death is an irreplaceable loss to those interested in the teachings of Professor. Just before his death, Tam had finished translating Professor’s commentary on the Lao Tzu. He was working on Professor’s interpretation and commentary of the “The Great Learning”, “Doctrine of the Mean”, and the “I Ching.” These things are lost to us. That’s one of the big tragedies of Tam’s early death.

Tam was a serious man with a great sense of humor. I know I’m not the only one to miss him. Thank you Tam.

—*—*—*—

Following are stories told by Tam C. Gibbs:

Professor Cheng dressed in the traditional clothing of a scholar (a robe falling below the knees, over a pair of pants, with a small skull cap), Tam and Ed boarded an empty subway car on the lower east side in New York. At the next stop a Hassidic Jew dressed in his traditional clothing (a robe falling below the knees, over a pair of pants with a small skull cap) boarded the subway car and sat down at the opposite end. Professor Cheng bent forward and looked left. At the same time the Hassidic Jew bent forward and looked right. Sitting back Professor Cheng asked, “Why is that man dressed so strangely?”

Sometimes after class Tam and a few others would go out to eat at one of Tam’s favorite Chinese restaurants. One night as we walked in Tam was greeted in Chinese by the owner and they had a brief conversation. Food was brought without being ordered. We ate it and as we were leaving, Tam thanked his friend and we left. As soon as we were outside he asked why none of us had said thank you. Our reply was none of us could speak Chinese. After an uncomfortable silence he asked, “Do you have to speak Chinese to be polite?”

One day Professor Cheng and Tam were walking in Riverside Park. Tam said to his teacher, “Tai Chi is difficult.” Professor Cheng’s response was, “Difficult? It’s just Tai Chi.” Several months later again they were walking in Riverside Park and Professor Cheng stopped Tam and said, “You’re right. Tai Chi is difficult.”

One day Professor Cheng and Tam were walking in Riverside Park. Professor Cheng stopped and said to Tam, “I’m getting better.”

As a young man in China, Professor Cheng met a man, a very strange man, who could sleep on a taut rope. Professor Cheng asked this man to teach him this skill to which this strange man replied, “Why do you want to learn to sleep on a rope? You know Tai Chi. You can help people. All I know is how to sleep on a rope.”

At one time Tam had a beard. One evening while eating with Professor and some of his distinguished friends, Tam stroked his beard. Professor Cheng smacked Tam’s hand away from his face and nothing more was said. When everyone had left, Professor told Tam that he needed to shave his beard because if you play with your beard, you are not mature enough to have one.